Behavioral Insights into Political Polarization in Christian Communities through Computational Modeling

This is a multidisciplinary work that involves a handful areas for study and a great deal of application. I will start by explaining what are agent-based models through some of my previous works. I will also talk about the methods for building behavioral models and the challenges when creating them. I will present then a draft for what is required to develop a model that account for the problem of Christian communities.

Introduction

We live in a time of increasing political polarization, where individuals and groups are often divided along ideological lines. This polarization can have significant implications for social cohesion, democratic processes, and the functioning of communities. In this context, understanding the dynamics of political polarization is crucial for fostering dialogue and promoting social harmony.

The de-churching phenomenon, characterized by the decline in church attendance and participation, has been a notable trend in recent years. This trend is particularly pronounced among younger generations, who are increasingly distancing themselves from traditional religious institutions. The reasons for this shift are complex and multifaceted, encompassing cultural, social, and personal factors.

In his recent book, The Great De-Churching, Jim Davis and Michael Graham explore the factors contributing to this phenomenon and its implications for society. They argue that the decline in church attendance is not merely a statistical trend but a reflection of deeper societal changes, including shifts in values, beliefs, and community engagement.

Bryan Chapell, in his book The Multigenerational Church Crisis: Why We Don’t Understand Each Other and How to Unite in Mission (2024), delves into the challenges faced by churches in bridging generational divides. He emphasizes the importance of understanding the perspectives and experiences of different age groups to foster unity and collaboration within congregations. He also points out that the de-churching process is not exclusive to younger generations, but also affects older generations, leading to a complex interplay of beliefs and practices within the church community.

The table below summarizes the key differences between the two generations, highlighting the contrasting values and priorities that contribute to the polarization within church communities:

| Aspect | Older Generation (Fifties and Older) | Younger Generation (Forties and Younger) |

|---|---|---|

| Perception | “We are (were) a majority” | “We are a minority” |

| Mission | Take control of culture | Make credible our faith |

| Means | Bring a halt to: (1) abortion (2) homosexual agenda (3) pornography (4) illegal drugs (5) gambling (6) green movement (7) illegal immigration (8) racial discrimination |

Help with: (1) adoption and foster care (2) care for and witness to LGBTQ+ persons (3) liberating victims of sex trafficking and sex addiction (4) substance addiction counseling and rescue (5) gaming and gambling addictions (6) creation care (7) refugee compassion and care (8) racial reconciliation and justice |

Even though recent research has shown that the church decline stabilized in the last years, it also shows a division and a preference for different types of churches based on demographic factors such as age, gender, and political affiliation. This division is particularly pronounced among younger generations, who are more likely to seek out churches that align with their values and beliefs.

Theoretical Framework: Polarization in Christian Communities

In his paper titled “Political Polarization and the Churches: Tocqueville on religion, democracy and future of Christianity”, Charles McDaniel Jr. presents a very interesting picture of the church according to the predictions of Alexis de Tocqueville. He argues that the church is a crucial institution for maintaining social cohesion and preventing political polarization. However, he also acknowledges that the church is not immune to the forces of polarization and that it can contribute to the fragmentation of society.

In this work they point out to one of Tocqueville’s sources, Father Mullon who worked as a missionary among Native American tribes in Michigan, saying he

posited an inverse relationship between religion’s influence in society and its involvement in politics, stating that the “less religion and its ministers are mixed up with government, the less they are involved in political debate, the more influential religious ideas will become”.

Dan White Jr. in his book Love Over Fear: Facing Monsters, Befriending Enemies, and Healing Our Polarized World (2020) argues that polarization is a pervasive issue in contemporary society, affecting not only political discourse but also personal relationships and community dynamics. He emphasizes the need for empathy, understanding, and love as antidotes to polarization, suggesting that these values can help bridge divides and foster reconciliation.

He defines polarization this way:

Polarization takes people that have something in common, emphasizes their differences, hardens their differences into disgust, and turns their disgust into blatant hatred. It creates two sharply contrasting groups and pits them against each other, shaping us for only two options—“our side” or “their side.” It’s a suffocating social arrangement. Polarization is a power and principality.

In his many examples of how he experienced polarization in his own life, he points out to a moment when two families left his church because of a feeling of threat due to the presence of others with a different political view. He says:

I grieved that both of these folks could not stay in the mix together. They were repelled by each other. Rather than moving toward one another, despite their differences, they chose more distance.

There is a common understanding on matters such as people’s opinions, beliefs, and behaviors that they are not static, but rather dynamic and subject to change over time. This is particularly true in the context of political polarization, where individuals’ views can shift in response to various factors, such as social influences, media exposure, and personal experiences.

But there is also an understanding that changes don’t come easily, and that people are often resistant to changing their opinions, especially when they are strongly held. This resistance can be driven by a variety of factors, including cognitive biases, social pressures, and emotional attachments to one’s beliefs.

In the context of Christian communities, this resistance to change can be particularly pronounced, as individuals may feel a strong sense of identity and belonging tied to their religious beliefs. This can make it difficult for them to engage with differing perspectives or to consider alternative viewpoints.

Fortunately, or unfortunately, we are people of the Bible. We take Jesus’ words seriously, even when they seem too naive or impractical.

You have heard that it was said, ‘Love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who hurt you, that you may be children of your Father in heaven… if you love those who love you, what reward will you get? . . . And if you are hospitable to only your own people, what are you doing more than others?” (Matt. 5:1, 43–48, Msg).

Jesus’ teachings on love and forgiveness challenge us to transcend our differences and embrace a more inclusive and compassionate approach to relationships. He calls us to love not only our friends and neighbors but also our enemies, urging us to pray for those who hurt us and to extend hospitality beyond our own circles.

But how does that lead us to models of Christian communities? How can we model the dynamics of political polarization in Christian communities, taking into account the teachings of Jesus and the complexities of human behavior?

Computational Approach Overview

Complex Systems

Our simulation requires a complex systems approach, taking into account the interactions between various agents and their environments. This involves modeling not only individual behaviors but also the emergent properties that arise from these interactions.

We consider that people’s opinions, beliefs, and behaviors are not static, but rather dynamic and subject to change over time. This is particularly true in the context of political polarization, where individuals’ views can shift in response to various factors, such as social influences, media exposure, and personal experiences.

Our model incorporates the dynamics based on social influences, media exposure and considers cognitive biases that can affect how individuals perceive and respond to differing viewpoints. This allows us to capture the complexities of political polarization in Christian communities, where individuals may feel a strong sense of identity and belonging tied to their religious beliefs.

Over time, our agents will interact with one another and with their environment, leading to emergent patterns of polarization and fragmentation. The model will include individual agents representing members of the community, each with their own beliefs and preferences. The agents will interact with one another and with their environment, leading to emergent patterns of polarization and fragmentation.

Agent-Based Modeling

Agent-based modeling (ABM) is a powerful computational approach that allows researchers to simulate the interactions of individual agents within a system. This method is particularly useful for studying complex social phenomena, such as political polarization, as it enables the exploration of how individual behaviors and interactions can lead to emergent patterns at the group level.

In other words, ABMs are computational models that simulate behavior of individual agents. ABMs are useful for studying emergent phenomena, where the behavior of the whole system is not simply the sum of the behaviors of its parts. They are particularly useful for studying complex systems, such as social networks, where individual behaviors can lead to unexpected outcomes.

One of the main benefits of ABMs is their ability to capture the heterogeneity of individual agents and their interactions. This allows researchers to explore how different behaviors and interactions can lead to different outcomes, such as the emergence of political polarization.

This method was originally developed in the 1970s and 1980s with models for social segregation, such as Schelling’s model of residential segregation. Since then, ABMs have been applied to a wide range of fields, including economics, ecology, and sociology.

ABMs receive different names in different fields, such as multi-agent systems, agent-based simulations, and agent-based computational economics. However, they all share the same basic principles of simulating the interactions of individual agents within a system.

Methodology

Methods for Building Behavioral Models

Building behavioral models involves several key steps, including defining the agents, their behaviors, and the environment in which they interact. The process typically begins with identifying the key components of the system being studied and determining how these components interact with one another.

Once the agents and their behaviors have been defined, the next step is to implement the model using a programming language or simulation platform. This involves coding the rules that govern the agents’ interactions and specifying how the model will be run.

The model can then be tested and validated by running simulations and comparing the results to empirical data or theoretical predictions. This process often involves iterating on the model design to refine the agents’ behaviors and improve the accuracy of the simulations.

Challenges in Creating Behavioral Models

Creating behavioral models presents several challenges, including the complexity of accurately representing individual behaviors and interactions. One of the main difficulties is capturing the diversity of behaviors and preferences among agents, which can lead to emergent patterns that are not easily predictable.

Another challenge is ensuring that the model is computationally efficient, as complex models can require significant computational resources to run. This can limit the scale and scope of the simulations, making it difficult to explore certain aspects of the system being studied.

Additionally, validating the model against empirical data can be challenging, as it requires access to high-quality data and a clear understanding of the underlying processes being modeled. This can be particularly difficult in social systems, where data may be sparse or difficult to obtain.

Finally, interpreting the results of the simulations can be complex, as emergent patterns may not have straightforward explanations. Researchers must carefully analyze the results and consider the implications for understanding the system being studied.

Proposed Model for Political Polarization in Christian Communities

In his paper titled “Political Polarization and the Churches: Tocqueville on religion, democracy and future of Christianity”, Charles McDaniel Jr. presents a very interesting picture of the church according to the predictions of Alexis de Tocqueville. He argues that the church is a crucial institution for maintaining social cohesion and preventing political polarization. However, he also acknowledges that the church is not immune to the forces of polarization and that it can contribute to the fragmentation of society.

In this work they point out to one of Tocqueville’s sources, Father Mullon who worked as a missionary among Native American tribes in Michigan, saying he

posited an inverse relationship between religion’s influence in society and its involvement in politics, stating that the “less religion and its ministers are mixed up with government, the less they are involved in political debate, the more influential religious ideas will become”.

Dan White Jr. in his book Love Over Fear: Facing Monsters, Befriending Enemies, and Healing Our Polarized World (2020) argues that polarization is a pervasive issue in contemporary society, affecting not only political discourse but also personal relationships and community dynamics. He emphasizes the need for empathy, understanding, and love as antidotes to polarization, suggesting that these values can help bridge divides and foster reconciliation.

He defines polarization this way:

Polarization takes people that have something in common, emphasizes their differences, hardens their differences into disgust, and turns their disgust into blatant hatred. It creates two sharply contrasting groups and pits them against each other, shaping us for only two options—“our side” or “their side.” It’s a suffocating social arrangement. Polarization is a power and principality.

In his many examples of how he experienced polarization in his own life, he points out to a moment when two families left his church because of a feeling of threat due to the presence of others with a different political view. He says:

I grieved that both of these folks could not stay in the mix together. They were repelled by each other. Rather than moving toward one another, despite their differences, they chose more distance.

There is a common understanding on matters such as people’s opinions, beliefs, and behaviors that they are not static, but rather dynamic and subject to change over time. This is particularly true in the context of political polarization, where individuals’ views can shift in response to various factors, such as social influences, media exposure, and personal experiences.

But there is also an understanding that changes don’t come easily, and that people are often resistant to changing their opinions, especially when they are strongly held. This resistance can be driven by a variety of factors, including cognitive biases, social pressures, and emotional attachments to one’s beliefs.

In the context of Christian communities, this resistance to change can be particularly pronounced, as individuals may feel a strong sense of identity and belonging tied to their religious beliefs. This can make it difficult for them to engage with differing perspectives or to consider alternative viewpoints.

Fortunately, or unfortunately, we are people of the Bible. We take Jesus’ words seriously, even when they seem too naive or impractical.

You have heard that it was said, ‘Love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who hurt you, that you may be children of your Father in heaven… if you love those who love you, what reward will you get? . . . And if you are hospitable to only your own people, what are you doing more than others?” (Matt. 5:1, 43–48, Msg).

Jesus’ teachings on love and forgiveness challenge us to transcend our differences and embrace a more inclusive and compassionate approach to relationships. He calls us to love not only our friends and neighbors but also our enemies, urging us to pray for those who hurt us and to extend hospitality beyond our own circles.

But how does that lead us to models of Christian communities? How can we model the dynamics of political polarization in Christian communities, taking into account the teachings of Jesus and the complexities of human behavior?

This work is an attempt to answer these questions by building a model that captures the dynamics of political polarization in Christian communities, while also considering the teachings of Jesus and the complexities of human behavior.

In the past years I’ve worked with cognitive models addressing the dynamics of social networks, such as the spread of crime in neighborhoods, the dynamics of cooperation, and the dynamics of health behaviors. These models have shown that individual behaviors and interactions can lead to emergent patterns at the group level, such as the emergence of polarization and the spread of misinformation.

Drawing from Schelling’s model of residential segregation, we can build a model that captures the dynamics of political polarization in Christian communities. The model will include individual agents representing members of the community, each with their own beliefs and preferences. The agents will interact with one another and with their environment, leading to emergent patterns of polarization and fragmentation.

This first attempt is a simple model that captures the dynamics of political polarization in Christian communities. The model includes individual agents representing members of the community, each with their own beliefs and preferences. The agents will interact with one another and with their environment, leading to emergent patterns of polarization and fragmentation.

In the past years I’ve worked with cognitive models addressing the dynamics of social networks, such as the spread of crime in neighborhoods, the dynamics of cooperation, and the dynamics of health behaviors. These models have shown that individual behaviors and interactions can lead to emergent patterns at the group level, such as the emergence of polarization and the spread of misinformation.

Drawing from Schelling’s model of residential segregation, we can build a model that captures the dynamics of political polarization in Christian communities. This work is an attempt to answer these questions by building a model that captures the dynamics of political polarization in Christian communities, while also considering the teachings of Jesus and the complexities of human behavior.

Model Overview and Implementation

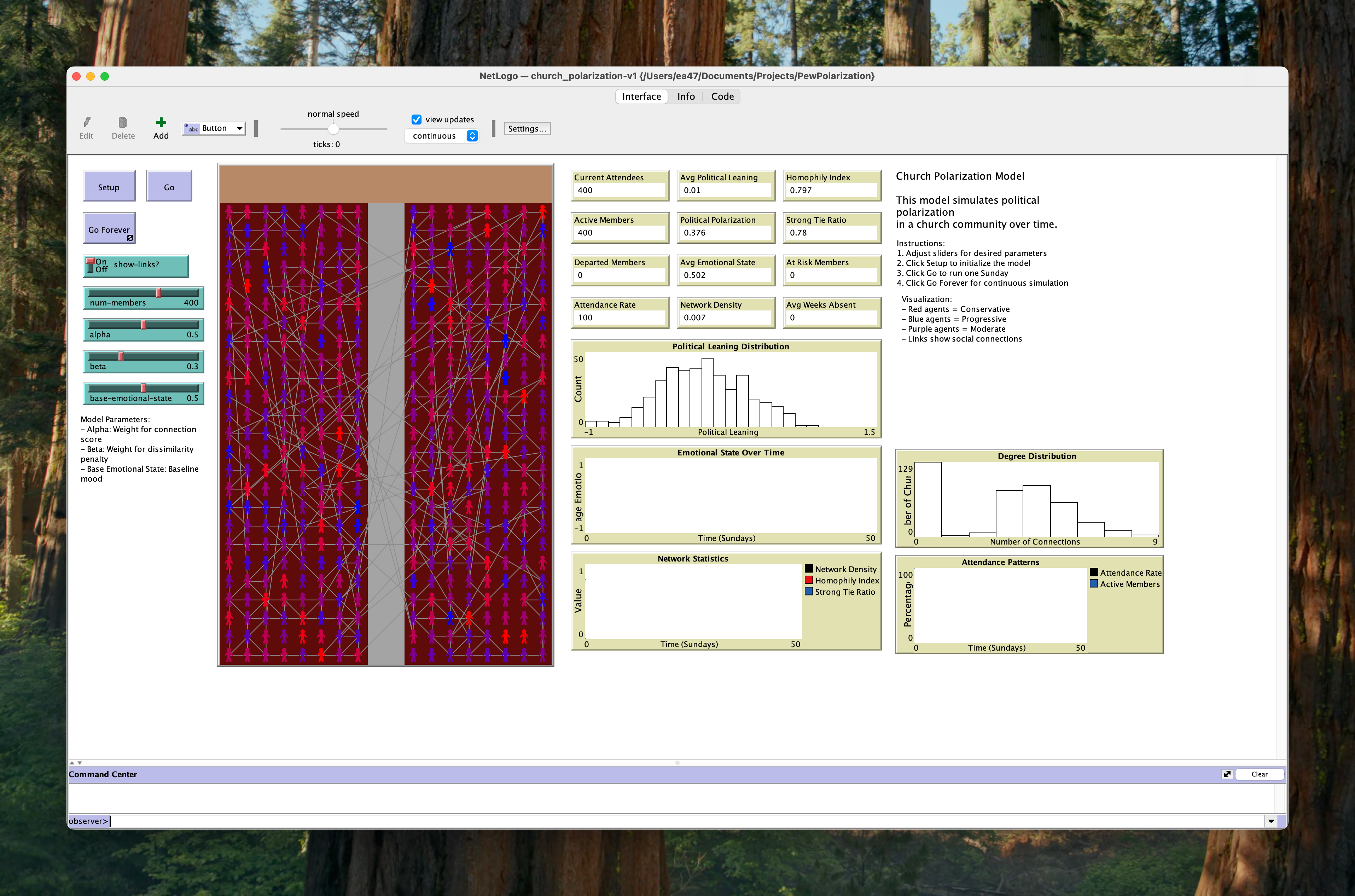

Our agent-based model represents a church community with 400 seats, where members attend Sunday services, interact with each other, and form or weaken social connections based on their political compatibility. Each simulation tick represents one Sunday service, allowing us to observe how polarization develops over weeks and months.

The model is built on the principle that political differences create tension in social interactions, which affects people’s emotional well-being and their desire to continue participating in the community. We implement this model using NetLogo 6.4.0, a powerful platform specifically designed for agent-based modeling.

posited an inverse relationship between religion’s influence in society and its involvement in politics, stating that the “less religion and its ministers are mixed up with government, the less they are involved in political debate, the more influential religious ideas will become”.

Dan White Jr. in his book Love Over Fear: Facing Monsters, Befriending Enemies, and Healing Our Polarized World (2020) argues that polarization is a pervasive issue in contemporary society, affecting not only political discourse but also personal relationships and community dynamics. He emphasizes the need for empathy, understanding, and love as antidotes to polarization, suggesting that these values can help bridge divides and foster reconciliation.

He defines polarization this way:

Polarization takes people that have something in common, emphasizes their differences, hardens their differences into disgust, and turns their disgust into blatant hatred. It creates two sharply contrasting groups and pits them against each other, shaping us for only two options—“our side” or “their side.” It’s a suffocating social arrangement. Polarization is a power and principality.

In his many examples of how he experienced polarization in his own life, he points out to a moment when two families left his church because of a feeling of threat due to the presence of others with a different political view. He says:

I grieved that both of these folks could not stay in the mix together. They were repelled by each other. Rather than moving toward one another, despite their differences, they chose more distance.

There is a common understanding on matters such as people’s opinions, beliefs, and behaviors that they are not static, but rather dynamic and subject to change over time. This is particularly true in the context of political polarization, where individuals’ views can shift in response to various factors, such as social influences, media exposure, and personal experiences.

But there is also an understanding that changes don’t come easily, and that people are often resistant to changing their opinions, especially when they are strongly held. This resistance can be driven by a variety of factors, including cognitive biases, social pressures, and emotional attachments to one’s beliefs.

In the context of Christian communities, this resistance to change can be particularly pronounced, as individuals may feel a strong sense of identity and belonging tied to their religious beliefs. This can make it difficult for them to engage with differing perspectives or to consider alternative viewpoints.

Fortunately, or unfortunately, we are people of the Bible. We take Jesus’ words seriously, even when they seem too naive or impractical.

You have heard that it was said, ‘Love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who hurt you, that you may be children of your Father in heaven… if you love those who love you, what reward will you get? . . . And if you are hospitable to only your own people, what are you doing more than others?” (Matt. 5:1, 43–48, Msg).

Jesus’ teachings on love and forgiveness challenge us to transcend our differences and embrace a more inclusive and compassionate approach to relationships. He calls us to love not only our friends and neighbors but also our enemies, urging us to pray for those who hurt us and to extend hospitality beyond our own circles.

But how does that lead us to models of Christian communities? How can we model the dynamics of political polarization in Christian communities, taking into account the teachings of Jesus and the complexities of human behavior?

This work is an attempt to answer these questions by building a model that captures the dynamics of political polarization in Christian communities, while also considering the teachings of Jesus and the complexities of human behavior.

In the past years I’ve worked with cognitive models addressing the dynamics of social networks, such as the spread of crime in neighborhoods, the dynamics of cooperation, and the dynamics of health behaviors. These models have shown that individual behaviors and interactions can lead to emergent patterns at the group level, such as the emergence of polarization and the spread of misinformation.

Drawing from Schelling’s model of residential segregation, we can build a model that captures the dynamics of political polarization in Christian communities. The model will include individual agents representing members of the community, each with their own beliefs and preferences. The agents will interact with one another and with their environment, leading to emergent patterns of polarization and fragmentation.

This first attempt is a simple model that captures the dynamics of political polarization in Christian communities. The model includes individual agents representing members of the community, each with their own beliefs and preferences. The agents will interact with one another and with their environment, leading to emergent patterns of polarization and fragmentation.

Agent Properties and Model Structure

Each church member in our model has four key attributes that drive their behavior:

Political Leaning: This ranges from -1 to +1, where negative values represent progressive views and positive values represent conservative views. We use a normal distribution with tanh transformation to ensure realistic political distributions while keeping values bounded.

Threshold Tolerance: This represents how much political difference an individual can tolerate in their interactions, ranging from 0 to 1. Higher values mean greater tolerance for political diversity.

Activity Level: This determines the probability that someone will attend church services, ranging from 0 to 1. This starts high but can decrease based on negative experiences.

Emotional State: This captures their current well-being level, also ranging from -1 to +1. This is the key outcome variable that determines whether someone stays or leaves.

The church environment is modeled as a realistic 400-seat sanctuary with 25 rows of pews. Each row has 16 seats arranged as 8 seats, then a center aisle, then 8 more seats. This spatial arrangement matters because people tend to interact more with those sitting nearby.

Church members are connected through a social network that represents friendships and regular social interactions. These connections are initially formed based on spatial proximity, political homophily, and regular attendance patterns. Each connection has two properties: tie strength, which measures relationship intensity, and political similarity, which tracks how compatible the connected individuals are politically.

Model Dynamics and Implementation

Each Sunday follows a five-step simulation cycle. Members decide whether to attend based on their activity level and emotional state. Attending members interact with others, following realistic patterns where they prioritize existing strong connections, then nearby neighbors, then random others. The quality of each interaction depends on political similarity and mutual tolerance, with these interactions affecting emotional states through our core mathematical model.

The heart of our model is the equation for updating emotional states:

Emotional State = Base + α × (Connection Score) - β × (Dissimilarity Penalty)

The base represents a person’s natural emotional baseline when attending church. Alpha (α) weights how much positive interactions with connected friends boost emotional state, while beta (β) weights how much negative interactions with politically different people hurt emotional state.

The social network evolves dynamically based on interactions. Connections can strengthen through positive shared experiences, new connections can form between people with high political similarity and positive interactions, and connections can weaken through poor interactions or missed attendance. This process typically leads to increasing political homophily over time.

Model Parameters and Departure Mechanisms

Members can permanently leave the church based on three factors: low emotional state (when consistently negative experiences occur), extended non-attendance (after 8 weeks of not attending), and very low activity level (when motivation to participate drops below 0.3). When someone leaves, they sever all social connections and disappear from the community, representing permanent departure rather than temporary absence.

The model has several key parameters that can be adjusted to explore different scenarios. Alpha (α) controls how much positive social connections matter for emotional well-being, while beta (β) controls how much political differences hurt emotional well-being. Church size can be varied from 50 to 600 members to explore how community size affects polarization dynamics, and base emotional state sets the baseline mood level for church attendance.

Model Outputs and Research Applications

The model tracks numerous metrics to assess polarization and community health, including attendance patterns, political metrics, emotional well-being, network statistics, and departure tracking. Agents are color-coded by political leaning (red for conservative, blue for progressive, purple for moderate), and social connections can be displayed to show network structure.

This model can be used to explore several important research questions about how different levels of political tolerance affect community stability, what role strong social connections play in preventing departures, and how community size affects polarization dynamics. The model also allows us to test interventions, such as increasing everyone’s tolerance or strengthening existing friendships.

Model Validation and Limitations

This model addresses real challenges facing religious communities today, as many churches report increasing political tension among members, with some people leaving due to political disagreements. The model helps us understand the mechanisms behind these dynamics - how individual psychology, social networks, and political differences interact to create community-level outcomes. While simplified, the model captures key processes: homophily in relationship formation, the emotional impact of political disagreement, and the cumulative effect of negative experiences leading to departure.

Like all models, this one has limitations. It simplifies complex human behavior and doesn’t capture many factors that influence church participation, such as theology, leadership, family connections, or external life events. Future extensions could include leadership effects, external events, belief change through social influence, and multiple communities. Despite these limitations, the model provides a useful framework for understanding how political polarization unfolds in close-knit communities.

Model Demonstration

This visual demonstration illustrates the model in action, showing the church layout with members color-coded by political leaning, social connections forming and evolving over time, real-time metrics showing polarization dynamics, and the effects of parameter adjustments. This helps demonstrate how individual behaviors aggregate into community-level patterns of polarization and fragmentation.

Conclusion and Future Directions

This agent-based model demonstrates how individual-level political differences can lead to community-level polarization and fragmentation. The key insight is that even small amounts of political friction, when accumulated over many interactions and many weeks, can drive people away from communities they once valued.

The model shows that both social connections and political tolerance play crucial roles in community stability. Strong friendships can buffer against political stress, while low tolerance for political differences can be destructive.

Most importantly, the model reveals that polarization is not inevitable - it emerges from the interaction of individual psychology, social network structure, and community dynamics. Understanding these mechanisms is the first step toward developing strategies to maintain unity in diverse communities.

This computational approach provides a bridge between the theoretical insights from Tocqueville, Dan White Jr., and Bryan Chapell, and the practical realities facing Christian communities today. It offers a tool for exploring interventions and understanding the conditions under which love can indeed overcome fear and polarization.